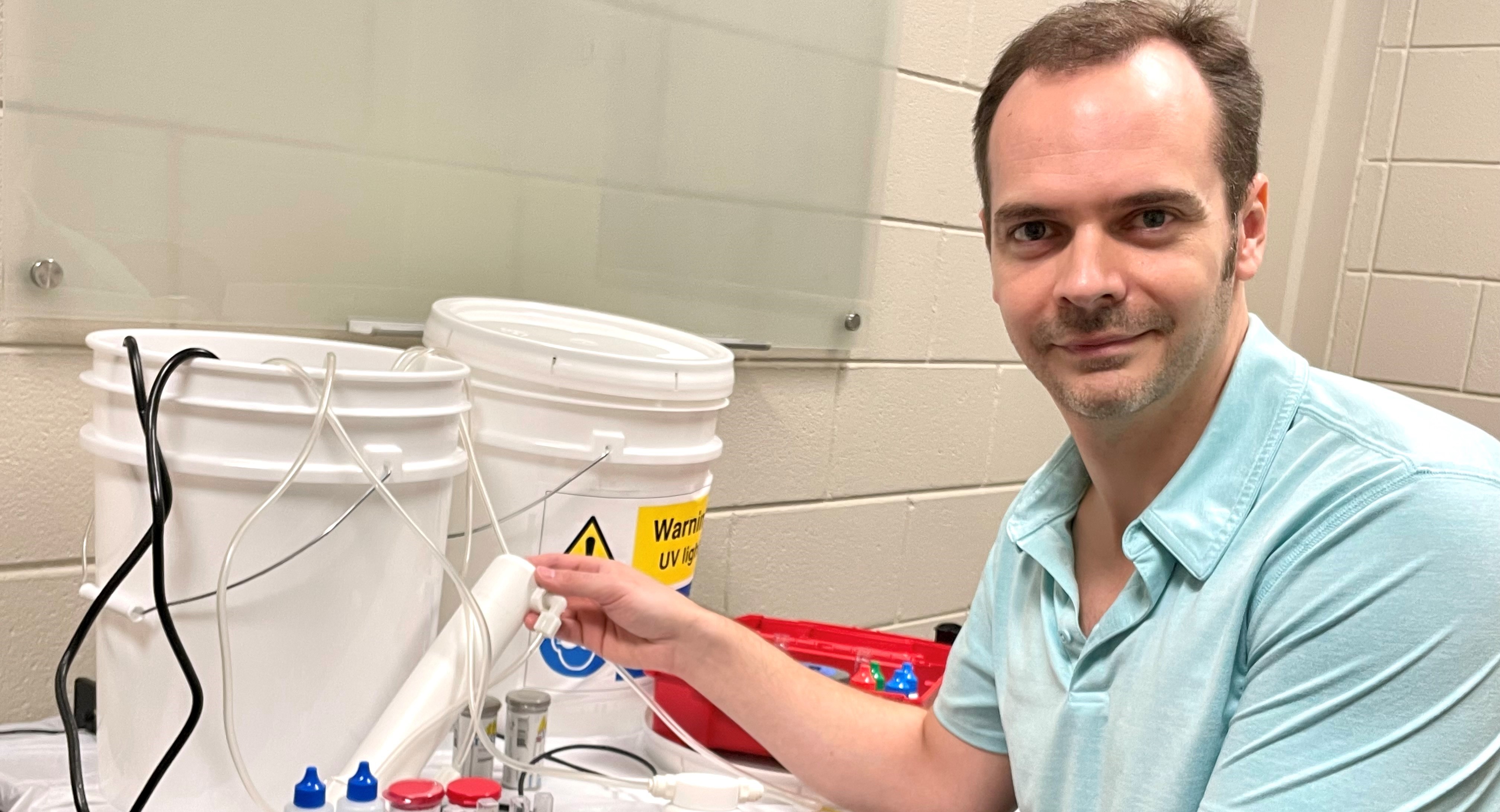

Ultraviolet (UV) light has proven invaluable during the Covid-19 pandemic, allowing frontline workers to disinfect hospital rooms, surfaces, and personal protection equipment (PPE) without the use of harmful chemicals. Robert Harris, a Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) engineer who developed portable UV disinfection chambers for PPE in 2020, is exploring additional ways to put UV technology to good use — including UV water disinfection, which he expects will have a direct impact on human health and safety as society prepares to tackle a future pandemic.

"[Covid-19] was so disruptive to life and the economy that I realized we need to focus technology development on emerging health threats and planning for the next pandemic," Harris said.

Harris developed an interest in UV water disinfection while working for a UV disinfection company from 2011 to 2013. While there, he helped develop and author the patent for the world's first flowing water UV disinfection system and gained firsthand knowledge of the engineering mechanisms behind designing and powering such a device.

Once Covid-19 became a widespread concern early last year, Harris was eager to put his knowledge of UV disinfection to work.

"I knew something about UV [and] UV LEDs (light-emitting diodes), and it was a tool that I knew existed for infection," Harris recalled. "At the beginning of the pandemic, nobody knew what would happen, and I thought, 'This is a tool that can help.'"

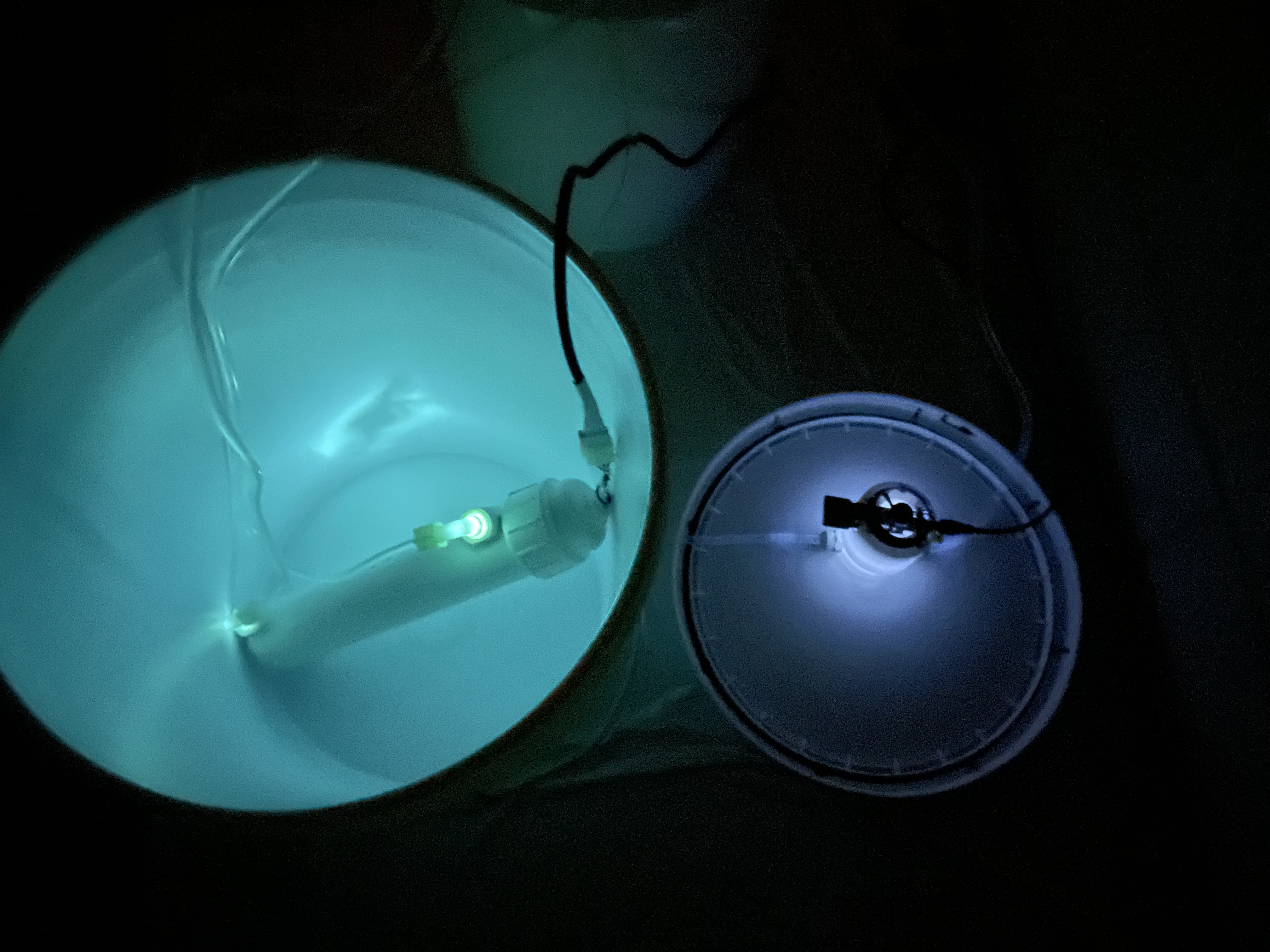

Ultraviolet water disinfection systems are already used in a number of commercial and consumer settings — including drinking water disinfection, swimming pool and wastewater treatment, as well as in the pharmaceutical and food and beverage industries — where consumer safety is a top priority. The technology specifically uses UV-C light, which works by deactivating the genetic makeup of bacteria and viruses found in water, air, and hard surfaces, and thus prevents those pathogens from multiplying and causing infection.

Harris considers UV surface, air, and water disinfection a safe solution for combating the spread of Covid-19 and other diseases. However, it does not come without its risks, including potential skin and eye damage in humans who are directly exposed, Harris noted.

Harris aims to use his research to educate more people on how to use disinfection technologies safely while also boosting their efficacy over longer periods of time. He also considers his research a health priority and hopes the use of UV treatment to create clean drinking water is given more attention going forward.

"Clean drinking water is something every human on the planet needs," Harris said.

In terms of efficacy, Harris' study partners with the UV industry to improve the long-term use of UV water disinfection systems and seeks solutions for making the systems last longer as their optical windows corrode and light sources age over time.

The UV water disinfection work further demonstrates GTRI's commitment to improving the human condition — not just in Georgia, but throughout the world — as outlined in GTRI's Strategic Plan for 2020 to 2030. GTRI remains dedicated to encouraging researchers to think outside the box when creating solutions for complex challenges. Through this approach, GTRI can deliver the highest level of impact throughout the world.

Another key component of GTRI's strategic plan is developing a pipeline of future technology leaders by fostering an environment where curiosity and innovation are celebrated.

Harris credited Shelby Claytor, a GTRI undergraduate research intern, for designing and executing many of the UV water treatment experiments. Claytor said the experience has provided her with a new skill set and challenges her to think critically about how to make the results gleaned from her experiments more accessible to others.

Harris has also been able to teach others how to use UV. Harris has collaborated with the Georgia Tech School of Chemistry and Biochemistry to provide solutions to a locally-based Fortune 500 company, using UV along with air filtration and aerosol solutions for public spaces.

"I created a calculator and simple simulator to show how to do this given a room size and number of people," Harris said. "There wasn't any guidance or rules of thumb in existence for how to do this."

A group of veterinary students at the University of Georgia recently formed a startup company called Automat, which produces self-disinfecting retractable non-slip pet exam table mats based on Harris' UV disinfection research. "We shared our electrical diagrams with them and helped to make sure that the UV was both human safe and effective against pathogens," Harris stated.

"GTRI's work with UV continues to lay the foundation of what is needed for design of UV surface, air, and water disinfection systems," Harris said.

Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is the nonprofit, applied research division of the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). Founded in 1934 as the Engineering Experiment Station, GTRI has grown to more than 2,700 employees supporting eight laboratories in over 20 locations around the country and performs more than $600 million of problem-solving research annually for government and industry. GTRI's renowned researchers combine science, engineering, economics, policy, and technical expertise to solve complex problems for the U.S. federal government, state, and industry. Learn more at https://www.gtri.gatech.edu/ and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Writer: Anna Akins

Photographer: Hunter Chan