Air Force Capt. Courtney Vidt had already spent more than a week in a classroom studying the nuances of aircraft physics, radar theory, and the numerous dangers posed to military transport aircraft like hers.

Now, the C-17 pilot was presented with a new challenge: Craft a mission plan for a mock exercise that would achieve the mission objective and get herself and her crew back home safely.

“We fly in a lot of areas where threats can reach out and touch us, and this course helps us be aware of what tools and tactics we have to prevent them from doing that,” Vidt said, “whether it’s flying around it, flying over it, flying under it, or other methods — so they can’t touch us.”

Vidt was one of about a dozen pilots and aircrew from multiple branches of the U.S. military who in March 2019 descended on Rosecrans Air National Guard Base, located about 60 miles north of Kansas City. They came for an advanced training course designed for the mobility air force — service members who fly the large military aircraft that carry people and supplies.

The course was taught at the Advanced Airlift Tactics Training Center (AATTC), which provides the highest level of training in defensive maneuvers, countermeasures, and tactics for mobility forces with the ultimate goal of keeping them safe while flying through potentially hostile skies.

But it’s not just military instructors in uniforms teaching those courses. Working alongside them is a team of experts from the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI), which for decades has partnered with mobility forces to develop technology to counter the threats that confront the military’s transport aircraft.

The GTRI team plays a pivotal role at the training center, helping students understand the science behind threats such as heat-seeking and radar-guided missiles as well as providing foundational knowledge of onboard aircraft systems and the measures used to defeat the threats.

“The goal of these courses is to save lives in the combat environment,” said Bobby Oates, a senior research scientist and GTRI’s site lead for the program at Rosecrans. “GTRI’s role here is to provide subject matter expertise. We’re all prior military aviators, and all of us have been on some sort of C-130 platform. That gives us a unique understanding of the needs of the mobility air force.”

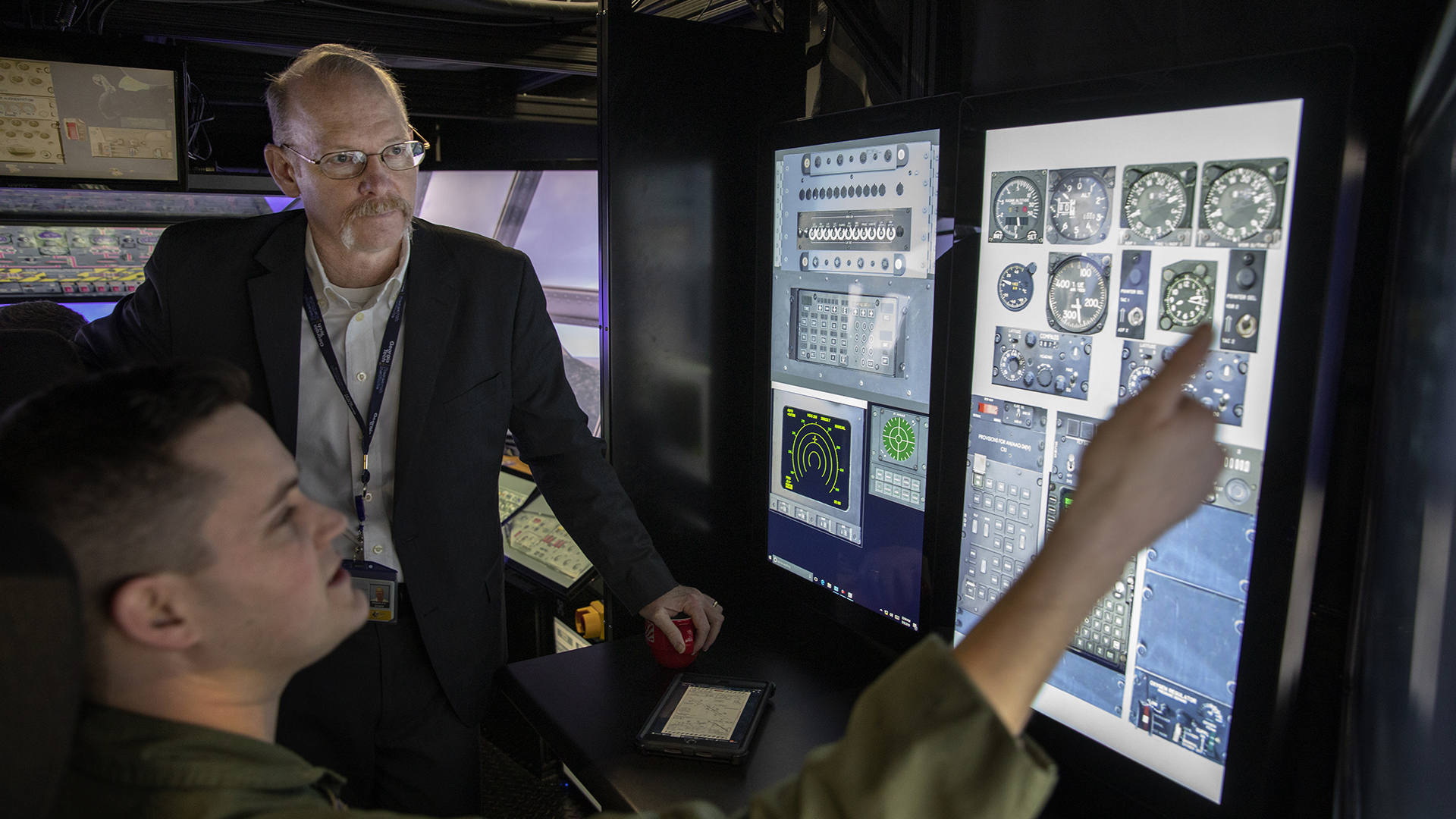

Master Sgt. Pedro McCabe (left), Lt. Col. Barrett Golden (middle), and Andrew Schoen (right), a GTRI senior research scientist, operate a C-130 flight simulator.

GTRI’s expertise is a key part of the instruction in all of the seven courses provided at the training center, as well as in the development of new tactics and maneuvers.

The team helps craft coursework and serves as a direct link between the training center and GTRI’s research, quickly turning new technical findings about threats or aircraft systems into new course material. Each team member specializes in specific subjects, staying in contact with on-campus researchers involved in those areas of study.

“Two members of our team are focused intensely on the infrared spectrum,” Oates said. “They are fully engaged in the current and emerging infrared threats, such as heat-seeking missiles, and they’re involved with the development of tactics to defeat those threats, whether through maneuvers or implementation of defensive systems and expendables such as flares. We also have two team members very involved in the radar side of the house. They are experts on radar threat technology and the employment of measures to defeat those threats.”

The training center has its origins in the early 1980s, when a Missouri Air National Guard unit flying C-130s at Rosecrans began conducting training to improve pilots’ ability to respond to threats encountered in combat. The school was formally established in 1983, initially focused on teaching pilots and aircrews defensive maneuvers and how to respond to threats while flying.

Those skills come in handy for pilots of the quad-turboprop engine C-130, which, because of its versatility and ability to land and take off in a variety of terrain, is one of the primary airframes the military uses to perform air drops and move cargo within hostile territory. The larger quad-jet engine C-17 provides a similar capability over longer distances.

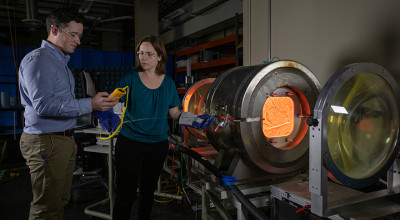

Rob Walling, a GTRI senior research engineer, highlights the components of expendable defensive measures.

The relationship between the training center and GTRI stretches back to the early years of the program, growing out of the research institute’s role in developing C-130 countermeasure systems such as flares. GTRI researchers would often travel to St. Joseph to provide guest instruction at the training center.

Over time, the partnership grew, with GTRI placing researchers fulltime, onsite at Rosecrans and eventually expanding to its current team of six experts now working side by side with the service members stationed there.

“The mission enhancement that comes with having that team of professionals here cannot be overstated,” said Col. Byron Newell, commandant of the training center. “It’s not inherent in being a pilot or a navigator or a combat systems operator to be subject matter experts on the science behind those systems.

“We are taught to flip switches, follow a checklist, and do things in a certain order and fly an airplane a certain way. But if you’re going to develop constantly evolving tactics and techniques to counter emerging enemy threats that are constantly changing, then you really need to understand the science behind those systems.”

Having the GTRI team on site at Rosecrans helps accelerate the transfer of technical developments and new scientific understandings of emerging threats from the broader GTRI research community into the classroom.

“We’re trying to think of it on our own in the Air Force, and often it is a young kid at college who has the right answer,” said Col. Deanna Franks, vice commandant of the training center. “Getting involved with people outside of our organization, and having the opportunity for them to field those answers to us, is the true importance and why we have such a great relationship with GTRI.”

Rod Orr, a GTRI senior research scientist, discusses navigation concepts inside a C-130 flight simulator with C-130H Navigator Capt. Justin Bigham.

In many ways, the GTRI staff there plays the role of translators between the mobility forces and the researchers in labs back on campus, both in front of the classroom and during the development of new tactics and systems.

“The folks on campus live and breathe this stuff, and it’s a great tool to be able to reach back and talk to them about what they’re doing,” said Rob Walling, a GTRI senior research engineer at Rosecrans and a former C-130 pilot. “We turn around and put it in terms aircrew can understand to go out and execute the mission and execute the tactic that was developed for them.”

The product of that relationship was on display in March for the course on tactics and mission planning, called Combat Aircrew Tactics Studies/Mobility Electronic Combat Officer Course, or CATS/MECOC, which is an intensive two-week course designed to train aircrew members to be tacticians who can help plan missions at their home units.

For the course, researchers from GTRI dive deep into the technical aspects of multiple aircraft defensive systems, such as radar warning receivers, which help alert aircrews of an approaching radar-guided missile. The researchers teach the science of how aircraft systems work, their strengths and weaknesses, how to best use them in a defensive situation, and how each aircraft’s capabilities come to bear from a mission planning standpoint.

“The level of instruction that we’re getting from this course is at a master’s — I would even dare to say Ph.D. level for some of it — just going in-depth with our airframe, in-depth with the threat picture out there, and understanding it,” said Vidt, the C-17 pilot who is stationed at Joint Base Lewis–McChord near Tacoma, Washington. “It’s a lot of information to process, and they know that. But they’re great in that they’re able to sit there, explain it to you if you have questions, and then help you put it into practical knowledge. That’s the most important part, not only learning it but being able to apply it.”

From left, Master Sgt. Amber Meyer, a flight engineer, Senior Airman Kevin Pajor, a loadmaster, Technical Sgt. Jesse Sunde, a loadmaster, and Maj. Charles Francis, a pilot, all from Minneapolis-St. Paul Joint Air Reserve Station, go over the details of a training mission.

The mock exercise was an opportunity for Vidt, who serves as a wing tactician at her home unit, to test whether she had absorbed the course material coming at her like a firehose for days as she sat alongside other pilots and aircrews of C-17s and C-130s.

“We had to figure out, how do I get my cargo from point A to point B when there are these threats out there, and what tools am I given to address those threats,” she said. “It’s thinking about the ‘ifs’ and the ‘whens’ and what could go wrong. And oh, by the way, there are also five teams working simultaneously on this mission, and how do we work together? How does the tanker provide fuel for all of us? How does my aircraft get to my mission when it has two other missions before it? It’s a puzzle.”

The AATTC trains students from the Air National Guard, Air Force Reserve Command, the active duty component of the United States Air Force, the United States Marine Corps, and international crews from across the globe.

Aircrew members have the option of completing multiple courses at the training center, and Vidt already has plans to return for the flying course.

“The more you’re exposed to something, the more you’re going to be able to understand it and apply it,” she said.

From its early years, the original flying course offered at Rosecrans evolved into the Advanced Tactics Aircrew Course, a two-week program designed to take aircrews not long out of flight school and prepare them to operate in a combat environment.

During the two weeks, the aircrews spend time in the classroom learning more about their aircraft, eventually taking that knowledge out to the planes to practice maneuvers while performing airdrops or flying low along mountain ridges during eight training missions split between Missouri and Arizona.

“As aviators, it’s very important to go out and actually practice these things that you’re doing,” said Capt. Will Jones, a C-130 pilot stationed at Dobbins Air Reserve Base near Marietta, Georgia. “The way the course starts, they give you the academics about mountain flying and how to use terrain to evade threats, but it really brings it together when you go out and fly the course and practice the techniques you learn in the classroom.”

C-130H Navigator Capt. Justin Bigham (left), C-130H Loadmaster Technical Sgt. Levi Justic (middle), and Kevin Valasek (right), a GTRI research associate, operate mission planning software.

The training center has designed the flying course to overlap with another offering at the school, a three-week course called the Advanced Airlift Mobility Intelligence Course, which provides intelligence officers advanced instruction on emerging threats. The course also teaches intelligence members and aircrews about gathering intelligence in a combat environment, enabling them to work together on mock exercises.

“When our aircrews fly, we brief them on the things that could potentially harm them and how they can mitigate those threats, stay safe, and return home,” said Lt. Col. Sue Vogel, an intelligence flight commander who helps instruct the intelligence course. “When they come back from that flight, we do a debriefing and gather all the information they got, and put it back out in the intelligence community and Georgia Tech so they have all that information and can update any threat tactics.”

GTRI experts are there to help explain the technology behind the threats and provide intelligence service members the tools they need to evaluate the threat level.

“One of the biggest things our students love about Georgia Tech is they take really hard subjects, like radar theory, and break them down so they’re very easy to understand,” Vogel said. “A lot of our students don’t deal with that on a daily basis, and they say, ‘Now I finally understand how that works, and now I can better support my crews.’”

For Col. Ed Black, the 139th Airlift Wing Commander and base leadership at Rosecrans, the relationship between GTRI personnel and the training center boils down to saving lives.

“You absolutely make a massive difference in our ability to survive as a country, and not only us but also our allied nations,” Black said. “There is no research project when we partner with GTRI that is insignificant. In our eyes, when we go for GTRI help on solving a problem, that is a massive problem for us, and your assistance in solving that problem — to put our forces in a better place to survive — has a direct impact on our national security.”

Josh Brown is a senior science writer at Georgia Tech. A journalist by training, he’s spent the past decade writing about economic development, medical research, and scientific innovation.

Josh Brown is a senior science writer at Georgia Tech. A journalist by training, he’s spent the past decade writing about economic development, medical research, and scientific innovation.