A team at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) has developed a small electronic sensing device that can alert users wirelessly to the presence of chemical vapors in the atmosphere. The technology, which could be manufactured using familiar aerosol-jet printing techniques, is aimed at myriad applications in military, commercial, environmental, healthcare and other areas.

The current design integrates nanotechnology and radio-frequency identification (RFID) capabilities into a small working prototype. An array of sensors uses carbon nanotubes and other nanomaterials to detect specific chemicals, while an RFID integrated circuit informs users about the presence and concentrations of those vapors at a safe distance wirelessly.

Because it is based on programmable digital technology, the RFID component can provide greater security, reliability and range – and much smaller size – than earlier sensor designs based on non-programmable analog technology. The present GTRI prototype is 10 centimeters square, but further designs are expected to squeeze a multiple-sensor array and an RFID chip into a one-millimeter-square device printable on paper or on flexible, durable substrates such as liquid crystal polymer.

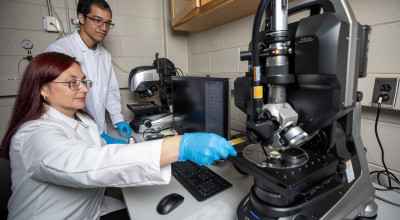

“Production of these devices promises to become so inexpensive that they could be used by the thousands in the field to look for telltale chemicals such as ammonia, which is associated with explosives," said Xiaojuan (Judy) Song, a GTRI senior research scientist who is principal investigator on the project. "This remote capability would inform soldiers or first responders about numerous hazards before they encountered them."

Wireless sensors could also be valuable for identifying and understanding air pollution, she said. Inexpensive sensors that detect ammonia and nitrogen oxides (NOx) could be fielded in large numbers, giving scientists increased knowledge of the location and intensity of pollutants.

The availability of such chips might also help companies detect food spoilage. And healthcare facilities could benefit, as the presence of telltale chemicals informed caregivers of patient conditions and needs.

The present prototype contains three sensors along with an RFID chip. Future devices for field use might contain a much larger number of sensors based on various nanomaterials – including carbon nanotubes, graphene and molybdenum disulfide – depending on the types of chemicals to be detected.

"In general, having an extensive sensing array is the best approach," Song said. "For real-world applications, a variety of sensors offers better functionality, because they can work together to produce a more detailed and reliable picture of the chemical environment."

The RFID component in the GTRI device makes use of the 5.8 gigahertz (GHz) radio frequency, one of several radio bands reserved for industrial, scientific and medical (ISM) purposes. The GTRI component is believed to be the first RFID system that exploits this frequency.

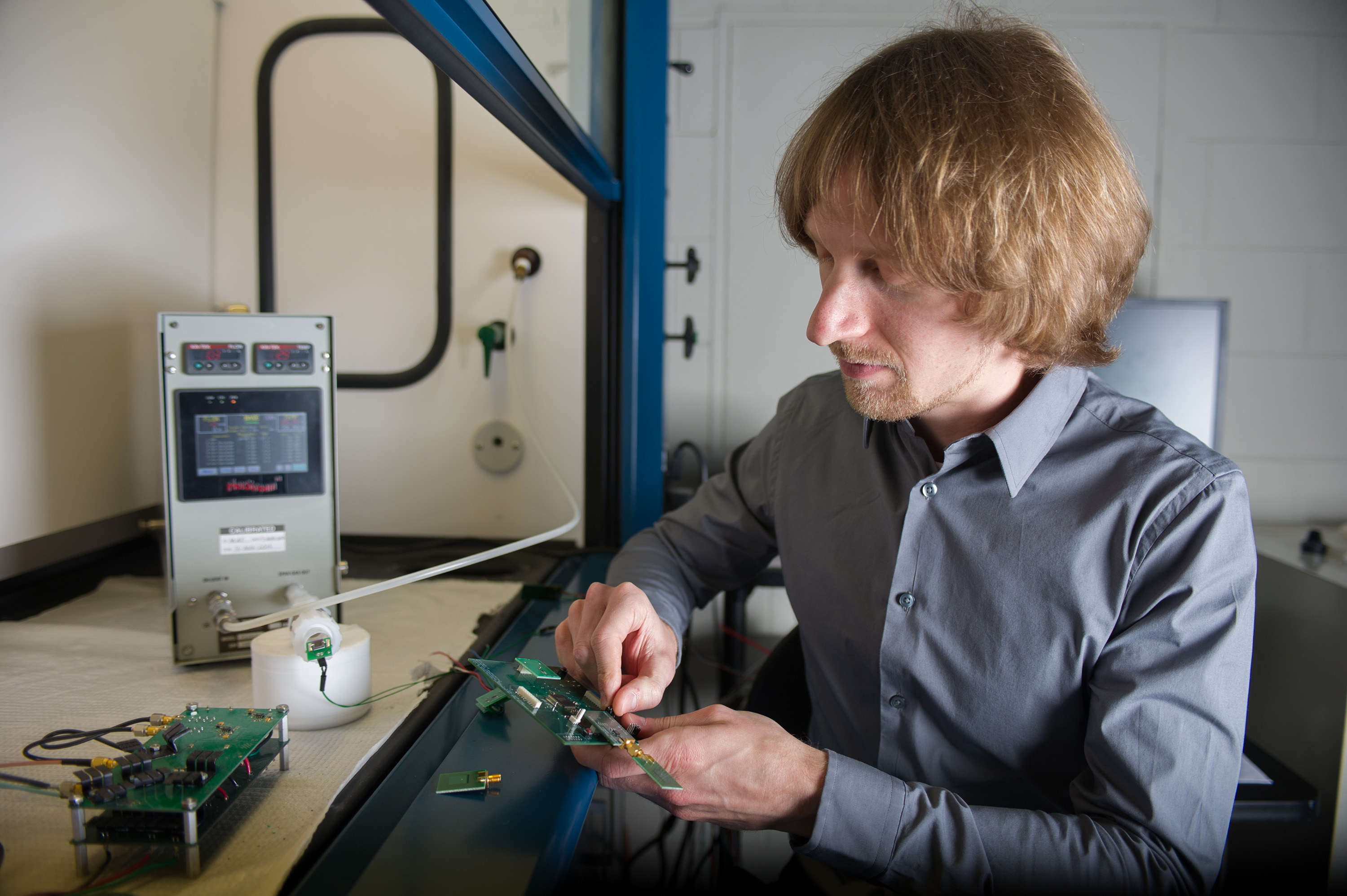

The advantage of 5.8 GHz technology is that it will let RFID tags be made extremely small – in the area of one centimeter square, said Christopher Valenta, a GTRI research engineer who is co-principal investigator on the project. He explained that the digital transmission of data from RFID-based sensors does a much better job than earlier analog techniques based on interpretation of radio-frequency waveforms.

Specifically, digital signaling with 5.8 GHz RFID offers:

- Greater security due to digital techniques that prevent unauthorized access to the wireless data stream;

- Increased resistance to interference from materials such as metals that can cause false readings;

- Digital-logic readings of chemical concentrations that are more precise and easier to interpret than analog approaches;

- Longer-range communication capability.

The GTRI team is currently gearing up to design a very small, 5.8 GHz RFID component. After fabrication and testing, the chip could be manufactured in large numbers inexpensively.

"It might take $400,000 to design and fabricate that first RFID chip, but all the subsequent copies might cost only a few pennies," said Valenta, who is a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

The GTRI team successfully tested its prototype sensing system in a demonstration designed to resemble an airport checkpoint. The sensor array detected the targeted chemical despite emersion in a complex chemical environment, and the RFID component was able to transmit the sensors' readings.

The present GTRI prototype is semi-passive, so it requires power from an incoming signal beam in order to send data back to a remote reading device. However, future sensing devices might exploit ambient energy from solar or vibrational sources that would let them work at longer ranges with greater sensitivity.

The team is continuing to work on the important task of developing pattern recognition software that will support effective functioning of the sensor array.

"The prototype 5.8 GHz wireless sensing system promises to be flexible and highly scalable," Valenta said. "An advanced design might include an array of 10 or more different sensors, with electronics that could utilize those sensors to perform 25 different jobs, and yet still be tiny, robust and inexpensive."