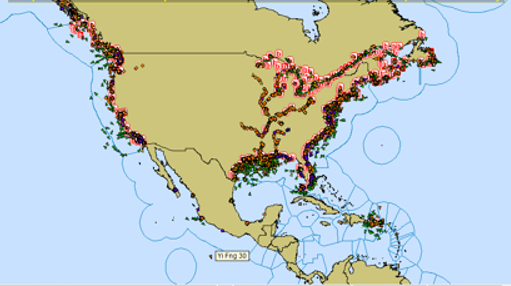

Cybersecurity improvements developed by the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) in collaboration with the U.S. Navy could soon help bolster protection for the Automated Identification System (AIS), which is used to track and identify commercial and military ships around the world.

AIS uses signals from transponders operating on the ships to help their captains avoid collisions when the vessels are outside of busy ports. Because AIS is based on an open standard developed many years ago, the U.S. Navy's Battlespace Awareness & Information Operations Program Office (PMW 120) realized the system needed hardening to help address current cybersecurity conditions and expectations.

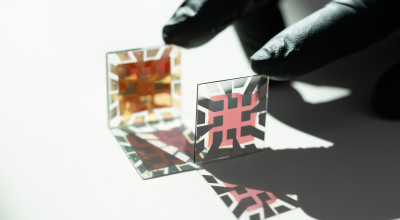

GTRI researchers were initially asked to evaluate potential vulnerabilities of the system, and then to develop an add-on software system, called Bifrost, which works with AIS to filter messages from ships, guard against potentially malicious messaging, and provide critical alerts to ship captains. The Bifrost system has been delivered to the Navy’s Battlespace Awareness & Information Operations Program Office, and is now undergoing evaluation – a step on the way to potential deployment.

“The goal of AIS is to avoid collisions, and everyone works together to contribute information about where their ship is and which way they are headed to make sure everyone can predict where they will be,” explained Shelby Allen, a GTRI research scientist who led the project. “Being able to trust the information being provided is important to ensuring the safety of maritime traffic worldwide. Along with GPS, AIS plays an integral role in how our forces operate across the seas.”

Information for AIS comes from transponders on each ship that provide such information as the GPS-based location coordinates, heading, and speed. The transponders use a common and open protocol, but equipment errors and other factors can affect the accuracy of what’s reported. Bifrost helps filter transponder information coming into Navy ships.

“The goal of the application we developed was not to get in the way of the existing system, since it is a critical path for downstream systems,” Allen explained. “We wanted to look for both accidental issues with the incoming transmissions and the potential for deliberate misuse.”

Because of the critical nature of the communications, the Bifrost system was designed to extract useful information from ship transmissions even if they don’t necessarily meet all the specifications of the protocol.

“The majority of what we see that looks like a transmission not abiding by the specifications are accidental formatting issues,” he said. “Filtering this information needs to have a certain amount of tolerance for what can go wrong and still have the messages provide useful information.”

Bifrost can detect deliberate misinformation, such as location updates that suggest speeds impossible for vessels to attain. “Ships can only accelerate and decelerate at certain rates, and there are some examples of egregious misuse of location information,” Allen said. “One of our goals was to detect messages less likely to be real GPS-based messages.”

Beyond cybersecurity hardening, Bifrost enhances how the system handles emergency alerts, which may not receive sufficient visibility in the original AIS interface.

“There are safety-related messages that by protocol should be addressed immediately,” Allen said. “We worked to make sure that these alerts had the smallest chance of being an annoyance. When someone did need to review the alerts and needed additional information, we made it as easy as possible to do.”

Because Bifrost was intended to be a working software system with an important safety mission, PMW 120 requested the researchers to carry development further than often happens with research projects. “We had to make sure that this was something that could quietly and reliably run for a long time in a performance environment,” he explained.

That reliability and operational testing extended a bit further than Allen originally expected – to ten days on a U.S. Navy guided-missile destroyer off the coast of California – and to bunk space reserved for researchers from organizations working on projects that required real-world testing at sea.

“At first, everybody was kind of learning their way around the ship and making sure they weren’t in anyone else’s way,” Allen said. “We slept in standard quarters and ate the same food everybody else onboard did. We were in the thick of operations on a Navy ship.”

Below deck, where Bifrost was operating, Allen and GTRI colleague David Myers at first lost track of time.

“One of the things I didn’t anticipate ahead of time was how optional it was to be outside,” Allen said. “When I imagined being on a ship, I imagined a huge deck with people there all the time. That was not true at all. The vast number of people are working beneath the deck, and there are multiple levels. There was a point I realized that it had been 24 hours since I had seen the sun.”

The researchers scheduled times to work with the operators of the system, knew when mealtimes were, participated in safety-related exercises, and took advantage of workout facilities – which required some adaptation to the rolling of the ship in the waves.

“There were beautiful, starry nights with absolutely no light pollution,” he said. “Dolphins were following the ship, just like in documentaries. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

Writer: John Toon (john.toon@gtri.gatech.edu)

GTRI Communications

Georgia Tech Research Institute

Atlanta, Georgia USA

MORE 2022 ANNUAL REPORT STORIES

MORE GTRI NEWS STORIES

The Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is the nonprofit, applied research division of the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). Founded in 1934 as the Engineering Experiment Station, GTRI has grown to more than 2,800 employees supporting eight laboratories in over 20 locations around the country and performing more than $700 million of problem-solving research annually for government and industry. GTRI's renowned researchers combine science, engineering, economics, policy, and technical expertise to solve complex problems for the U.S. federal government, state, and industry.