Five different types of solar cells fabricated by research teams at the Georgia Institute of Technology have arrived at the International Space Station (ISS) to be tested for their power conversion rate and ability to operate in the harsh space environment as part of the MISSE-12 mission. One type of cell, made of low-cost organic materials, has not been extensively tested in space before.

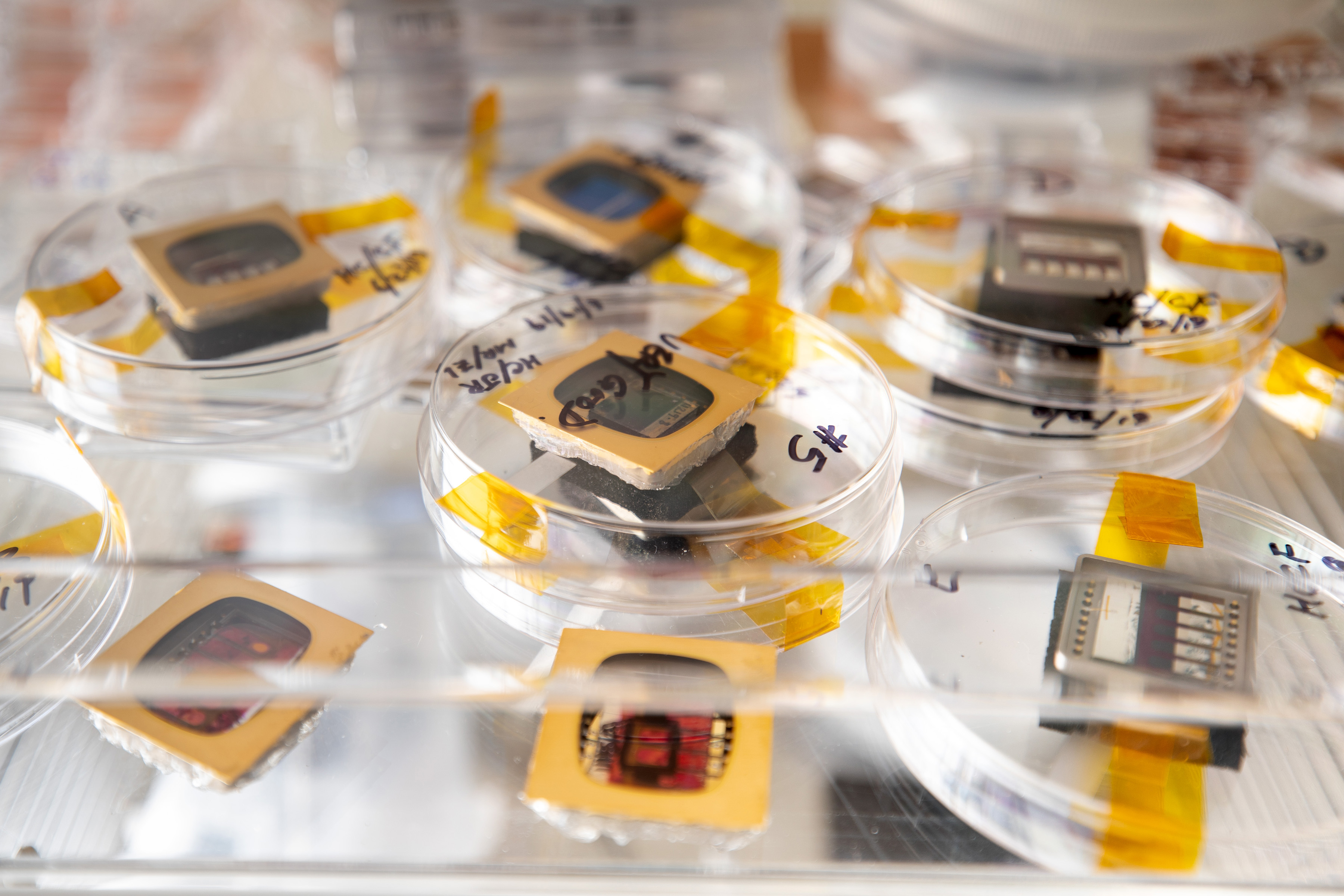

Textured carbon nanotube-based photovoltaic cells designed to capture light from any angle will be evaluated for their ability to efficiently produce power regardless of their orientation toward the sun. Other cells made from perovskite materials and a low-cost copper-zinc-tin-sulfide (CZTS) material – along with a control group of traditional silicon-based cells – will be among the 20 photovoltaic (PV) devices placed on the Materials International Space Station Experiment Flight Facility on the exterior of the ISS for a six-month evaluation. For two of the cells, the launch marked their second trip into space.

“The research questions are the same for all the photovoltaic cells: Can these photo-absorbers be used effectively in space?” said Jud Ready, principal research engineer in the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI), associate director of Georgia Tech’s Center for Space Technology and Research, and deputy director of Georgia Tech’s Institute for Materials. “With this test, we will gain insights into the degradation mechanisms of these materials and be able to compare their power production under varying conditions.”

Organic solar cells developed in the laboratory of Professor Bernard Kippelen at Georgia Tech are processed at low temperatures using solution-based processes over large areas to produce cells with an absorber that can be about 200 times thinner than the width of a human hair.

“With a very low weight and power conversion efficiency values of up to 16%, organic solar cells could yield power values in the hundreds of thousands of watts per kilogram of active material, which is very attractive for space applications,” said Kippelen, the Joseph M. Pettit Professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “However, the effects of continuous exposure of these devices in a space environment have not been thoroughly explored. Our interest is in investigating the robustness of the interfaces formed in these devices in a space environment, as well as to improve our understanding of the mechanisms of degradation for organic solar cells in space.”

Traditional flat solar cells are most efficient when the sunlight is directly overhead. Because the direction of the solar flux varies with the orbit, large space vehicles like the ISS use mechanical pointing mechanisms to keep the cells properly aimed. Those complex mechanisms create maintenance issues, however, and are too heavy for use on very small spacecraft such as CubeSats.

To overcome the pointing problem, Ready’s team developed 3D textured solar cells that can efficiently capture sunlight arriving at different angles. The cells use “towers” made from carbon nanotubes and covered with PV material to trap light that would bounce off standard cells when they are not angled toward the sun.

“With our light-trapping structure, we are agnostic to the sun angle,” said Ready. “Our cells actually work better at glancing angles. On CubeSats, that will allow efficient capture regardless of the orientation of the sun.”

Perovskite cells produced in the laboratory of Zhiqun Lin, professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering, will also be tested. These materials have known failure mechanisms caused by moisture and oxygen absorption. “These two failure mechanisms won’t be present on the outside of the International Space Station, so this test will allow us to see the performance of these materials without those issues. We should be able to determine whether these known issues might be masking other degradation causes,” Ready said.

CZTS materials are potentially next-generation solar cells made up of low-cost, Earth-abundant materials: copper, zinc, tin, and sulfur. The materials have a high absorption coefficient and may be resistant to radiation – useful for space applications – and offer an attractive tradeoff between cost and performance, Ready said.

Silicon-based solar cells produced by the University Center of Excellence in Photovoltaic Research and Education at Georgia Tech will provide a way to compare the performance of the other cells. The laboratory, headed by Professor Ajeet Rohatgi from the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, provided boron-doped p-type cells with a phosphorus-doped n+ emitter and aluminum-doped p+ back surface field.

“These silicon photo-absorber cells will serve as controls to compare the performance of other photo-absorber materials in space,” said Rohatgi.

The 20 PV cells will briefly join three other cells fabricated by Georgia Tech researchers that are already on the ISS. Those three, and two on the newest mission, were part of a 2016 experiment that was unable to record data, though it did provide information about the effects of the space environment on the solar cells.

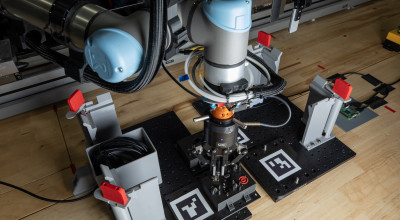

The Georgia Tech photovoltaic cells were launched to the ISS on Nov. 2 aboard the S.S. Alan Bean, a Northrop Grumman Cygnus spacecraft from NASA’s Wallops Island Facility, as part of a routine resupply mission. For their testing, the cells were integrated into a test package by Alpha Space Test & Research Alliance of Houston.

In addition to those already mentioned, the project also included Canek Fuentes-Hernandez, Matthew Rager, Hunter Chan, Christopher Tran, Christopher Blancher, Zhitao Kang and Conner Awald and Brian Rounsaville, all from Georgia Tech.